Appelflappen and Clog Wogs. On Flemish and Dutch Emigrants in the Anglophone World

Dutch and Flemish people who move abroad to Anglophone countries don’t speak Dutch quite as often as their other emigrated compatriots do. There are, however, far more clubs and social activities for emigrants from the Low Countries in the Anglo-Saxon world. This has become evident thanks to Vertrokken Nederlands (Emigrant Dutch), the very first global study on the preservation or loss of Dutch language, culture, and identity.

At the end of 2019, a study was published on the question of how important Dutch language and culture is for 21st century Dutch and Flemish emigrants. This study, called Vertrokken Nederlands (Emigrant Dutch), was conducted under my leadership by the Meertens Institute and the Taalunie (Dutch Language Union). The results illustrated that for the vast majority of Dutch and Flemish emigrants, Dutch language and culture continues to play an important role in their daily lives.

Over 85% of participants consider the Dutch language to be a core facet of their identity

Dutch remains one of the most used languages by emigrants in their country of residence: 97% of the participants said they speak Dutch every week, of which 64.6% speak more than eight hours a week, mainly in private situations or on social media. The majority of participants see Dutch as the language they know best, and over 85% of participants consider the Dutch language to be a core facet of their identity. This is surprising: existing research into 20th century emigrants has shown that this group often gave up their mother tongue within two or three generations of emigration – fairly quickly. In the 21st century, this is no longer the case.

Thanks to the internet

The fact that emigrants are holding onto their Dutch these days is largely thanks to the internet. After all, the internet makes it possible to follow Dutch news, read Dutch books, enjoy Dutch television, listen to Dutch radio shows, and communicate with Dutch-speakers on social media and in Dutch-language communities online. None of these options were available in the 20th century.

The internet has also made way for the Vertrokken Nederlands project – it had not previously been possible to conduct such large-scale, global research among emigrants. When disseminating its surveys on language preference, cultural habits, and language use to emigrants abroad, Vertrokken Nederlands took advantage of two newly available networks: Facebook, as well as communities of researchers in their respective countries of residence. Using these channels to reach participants has produced remarkable results: the surveys were completed by nearly 7,000 emigrants living in 130 different nations.

Popular countries of residence

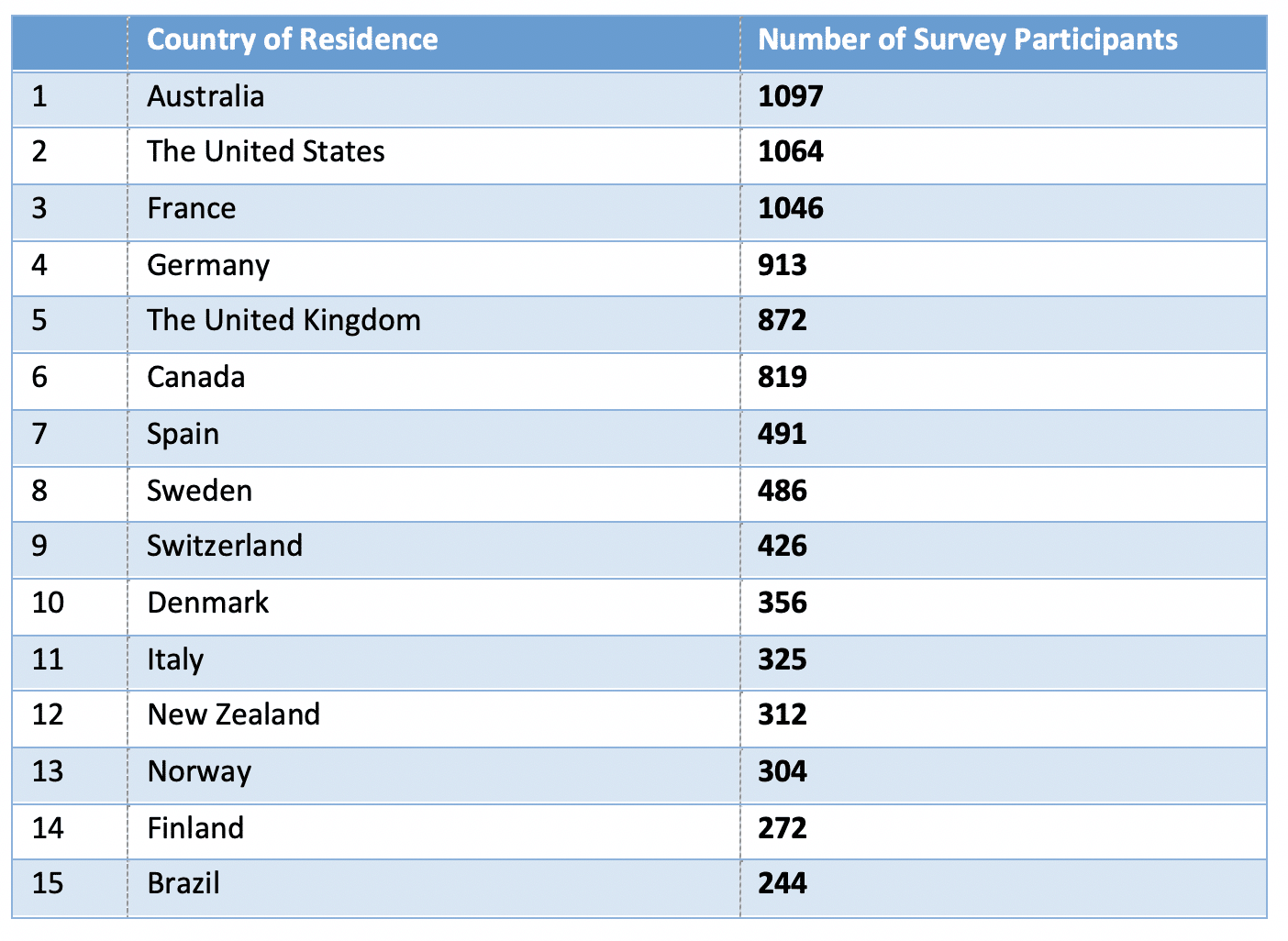

Figure 1 lists the fifteen countries that produced the largest number of survey responses. And no less than one third of these top fifteen countries are nations where English is counted among the official languages: Australia (1), the United States (2), the United Kingdom (5), Canada (6), and New Zealand (12). The number of participants from Canada who live in the English-speaking part of the country, however, is unknown.

Figure 1: The fifteen countries producing the largest number of survey responses

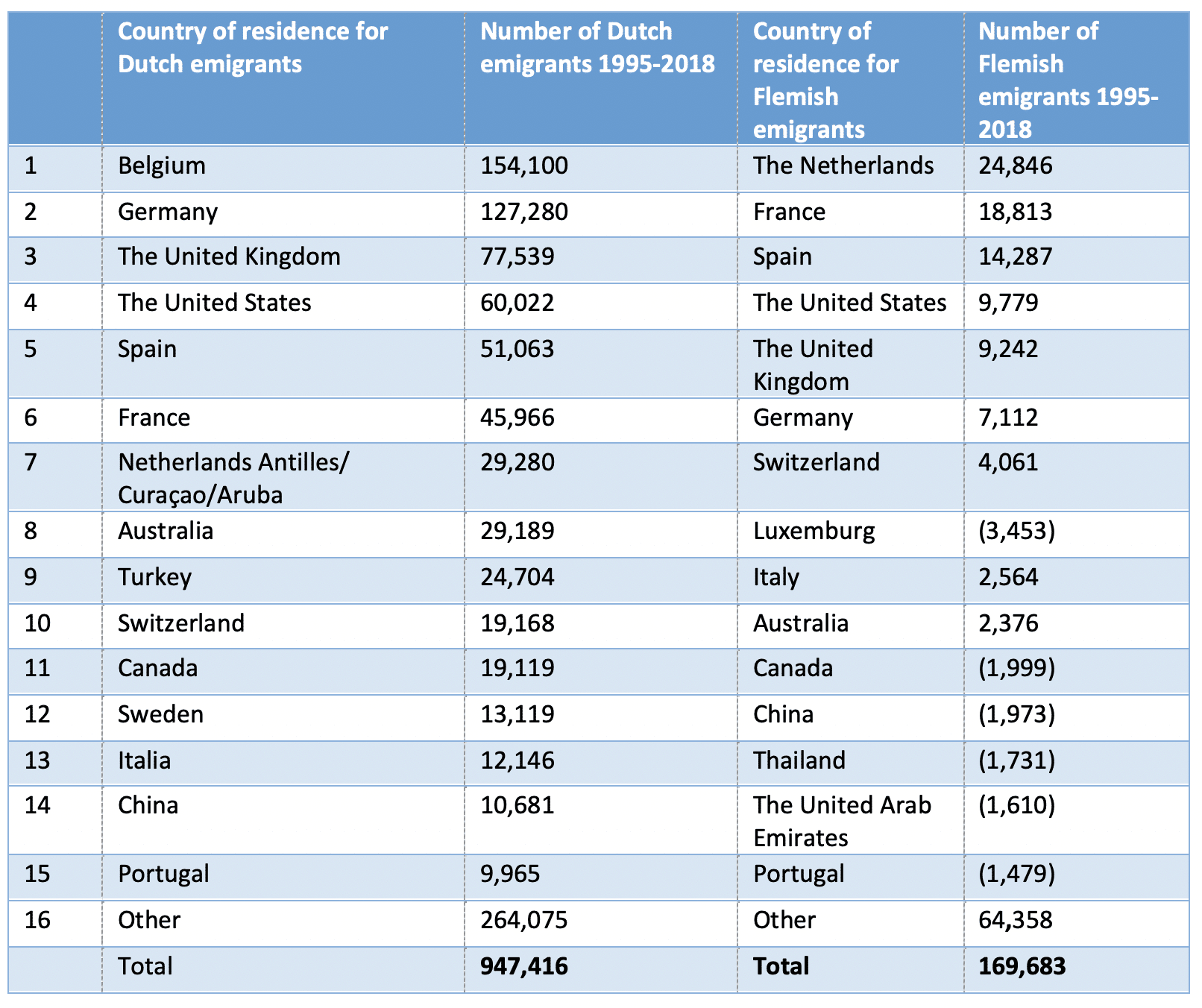

Figure 1: The fifteen countries producing the largest number of survey responsesIn comparison, Figure 2 provides an overview of the fifteen countries where the most Dutch and Flemish emigrants have settled since 1995, according to data provided by the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) and Statbel, the Belgian statistical office (the latter offering only data concerning emigrants born in Flanders). This table reveals that the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, and Canada are among the top fifteen countries of choice for Dutch and Flemish people who settle abroad. The extensive pattern of emigration from the Netherlands to Australia, the United States and Canada is in part due to the fact that the Dutch government stimulated (or at least facilitated) emigration to these areas post-1945. But even after such government schemes were ended, the rate of emigration to these countries has remained high.

The extensive pattern of emigration from the Netherlands to Australia, the United States and Canada is in part due to the fact that the Dutch government stimulated (or at least facilitated) emigration to these areas post-1945.

The extensive pattern of emigration from the Netherlands to Australia, the United States and Canada is in part due to the fact that the Dutch government stimulated (or at least facilitated) emigration to these areas post-1945.When it comes to emigration from the Netherlands, New Zealand, at number sixteen, falls just outside the top fifteen countries of choice. Meanwhile, there was no data available from Statbel as to the number of Flemish people who have emigrated to the archipelago. Emigration to countries on other continents where English is among the national languages, like those in Asia and Africa, is relatively limited, and beyond the scope of this article.

Figure 2: The fifteen countries with the largest number of Dutch and Flemish emigrants

Figure 2: The fifteen countries with the largest number of Dutch and Flemish emigrantsIn general, the reach of the surveys was found to correspond relatively well to the number of actual emigrants to each particular country: the majority of the survey responses were sourced from two thirds of the countries featured in Figure 2, namely Australia, the United States, France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and Italy.

It is worth noting that Belgium ranks first among Dutch emigrants, and that the Netherlands ranks first among Flemish emigrants, but that these emigrants hardly completed the surveys. Such border migrants apparently did not feel compelled to participate in the surveys, perhaps because of the close geographic distance between their country of birth and their new country of residence, and because the language and culture are more or less the same. Still, one of the emigrants did share from personal experience that “for a Dutch person, a move to Belgium is really a move abroad.”

Who are the emigrants?

The profile of the survey participants breaks down as follows: the average age was around fifty; slightly more women than men took part; most of the participants completed the survey for themselves; 55% of the participants emigrated in the 21st

century; and the participants were generally highly educated – over 75% had a diploma of higher education, most of them obtained in the Netherlands or Flanders. The vast majority of participants were originally born in the Netherlands, while Flemish emigrants were in the minority. It is possible that we failed to reach the latter group because there are far fewer Facebook groups and pages dedicated to Flemish emigrants. Descendants of emigrants were also in the minority of respondents.

The participants were generally highly educated – over 75% had a diploma of higher education

Most emigrants maintain contact with their country of birth in one way or another. For example, 88.4% of the participants visit the Netherlands or Flanders one or more times every five years. However, only 12.9% of the participants plan to return in the long term. Around 60% of emigrants are members of a Dutch or Flemish association in their place of residence, or are members of a Dutch or Flemish online community, such as a Facebook group.

There are all kinds of dedicated Facebook groups for Dutch and Flemish migrants in the Anglophone world. No fewer than thirteen groups cover the community in the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland. These groups are also regionally oriented or aimed at specific target groups, as shown by names like: ‘Dutch People in Scotland’, ‘Dutch Girls in London’, ‘Dutch People Across the Way’ (people from NL in the UK), ‘Dutch People in Ireland and the UK, ‘Dutch People in Nottingham’.

Surprisingly, there are no Facebook groups targeted specifically at Flemish emigrants to the United Kingdom, though a substantial number of Flemish people are based there. The same is true for the seven Facebook groups in the United States: they are all aimed at Dutch emigrants, not at Flemish emigrants. Meanwhile there are nine Facebook groups in Australia, three in Canada, and two in New Zealand – some of them for Dutch people, some of them for Flemish people.

Remarkably, there are no Facebook groups in the above-mentioned countries targeted at both Dutch and Flemish people alike. In Australia, for example, the groups ‘‘Dutch People in Australia’, ‘Dutchies in Melbourne’, and ‘Dutch People in Sydney’ exist alongside the groups ‘Belgians in Australia’, ‘Belgians in Melbourne’, and ‘Belgians in Sydney’. You would expect for emigrants with the same mother tongue and a largely identical culture to want to seek each other out abroad, but this is not the case. In non-Anglophone nations, however, there exist groups like ‘Dutch and Flemish People in the Philippines’, ‘Dutch and Flemish People in Spain’, and ‘Dutch Speakers in Slovakia’.

Beyond Facebook groups, the most organized infrastructure for communication among emigrants is found in the countries that were traditionally chosen by Dutch and Flemish people throughout the 20th

century – Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. Examples in Canada are Dutch Network and the Canadian Association for the Advancement of Netherlandic Studies; in the United States The Dutch International Society, the Nederlands America University League, and De Krant (The Paper); in Australia the Dutch Australian Cultural Centre, Dutch Courier, Dutch TV, and SBS Dutch Radio.

Dutch language use

The surveys asked participants how many hours per week they spend speaking Dutch. It appears that Dutch is used the least in Australia, the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, while it is used the most in France, Germany, and Spain. This pattern is found replicated in the responses regarding language use with children and on social media. In both cases, the use of Dutch in the Anglophone world scores the lowest.

There are several reasons for the less frequent use of Dutch in countries like Canada, the United States, New Zealand and Australia, which were favoured by immigrants in the 20th

century. Indeed, many respondents had emigrated in the 20th century, a period marked by a strong, government-backed assimilation policy – as much by the Dutch government as by the host country’s government. It was highly encouraged for people to make the switch to English quickly. Now, English has become the international language of trade, science, entertainment, and music, and is such an important school subject that most Dutch and Flemish people already speak English quite well by the time they emigrate, making it easier to pick up further once there.

Most Dutch and Flemish people already speak English quite well by the time they emigrate

Although emigrants in Canada, the United States, New Zealand, and Australia speak Dutch less frequently compared to elsewhere, these are also the countries that boast the largest number of clubs who organize social activities for emigrants from the Low Countries. It is at these events where Dutch-speaking emigrants come together for coffee clubs, Sinterklaas gatherings, and to celebrate Koningsdag (King’s Day), or Oranjefeest (Orange Day). One participant from Grand Rapids, Michigan noted that while they do celebrate Sinterklaas, “it has become a very different kind of children’s party”.

To celebrate and commemorate their historic ties to the Netherlands, these countries also host special holidays: Dutch-American Heritage Day in the USA (16 November), Canada’s Dutch Heritage Day (5 May), and New Zealand’s Tulip Day at the Wellington Botanical Gardens – celebrated upon the tulips’ first bloom. Tulip festivals in particular can be found in Canada and the States too, the largest being the Tulip Time Festival in Holland, Michigan.

The perception of the Dutch-speaking emigrant

One of the survey questions posed by Vertrokken Nederland asked for common jokes or stereotypes encountered by Dutch and Flemish people abroad. The answers from the Anglophone world were fairly uniform and cliché: the most characteristic Dutch traits were stinginess and thrift. Several respondents pointed to the expressions “Dutch treat” or “going Dutch” – to split costs according exactly to what one owes. Other respondents referred to the joke that “Dutch people’s pockets are so deep that they can’t even reach their money”; and “It’s so cheap, a Dutch person would buy it”; or “How was barbed wire invented? Two Dutchmen fighting over a coin.”

The directness, arrogance, and rudeness of the Dutch also came up often: they speak their mind plainly (“talking like a Dutch uncle”). They don’t need “drunk courage” because they already have “Dutch courage”. But their directness is also seen as a positive quality: “You know where you’re at with the Dutch. They can be bloody rude, but they speak their mind.”

In Australia, the Dutch are called Clog Wogs

In Australia, the Dutch are called Clog WogsThe supposed stubbornness of the Dutch has led to some creative new puns too: “Wooden shoes, wooden head, wouldn’t listen”, and “Those Dutch with their wooden shoes, wooden bridges, and wooden houses. The problem with them is that they wouldn’t listen”. In Australia, the Dutch are called Clog Wogs: a mash-up of clog – “wooden shoe” – and wog – “foreigner or immigrant”.

Inevitably, with it’s many hard g’s, the Dutch language also garners attention from English speakers. One participant says that his mother-in-law “makes a spectacle of her pronunciation of appelflappen to underline just how impossible the language is for her.” In the Anglophone world, double Dutch becomes synonymous with “talking nonsense” or “unintelligibility.”

Although the dike stereotype innocently refers to the children’s book in which Hansje Brinker prevents a horrible flood, to speak of the Dutch putting their fingers in dikes or swimming in the dikes takes a different meaning in Australia, where dike is slang for “toilet”. Meanwhile, to fart under the covers is called a “Dutch Oven”. And finally: “What do a wise Dutchman and God have in common?” Answer: “Neither of them exist.”

These jokes are all good-natured and in good fun, because ultimately, the perception of the Dutch among their new countrymen is very positive, as is evident from the proverbial expression: “If it ain’t Dutch, it ain’t much”, or even “If you ain’t Dutch, you ain’t much”. Though there are inevitably the jokers who flip it back around with “if you’re Dutch you ain’t much”.

Digital information

One important discovery that emerged from this research was the need among participants for support from the Low Countries in the field of Dutch-language education, and information about Dutch language and culture. The report therefore concludes with the intention to investigate the potential for a digital information center about Dutch language, culture, and education, specifically aimed at emigrated Dutch and Flemish people abroad. Work is currently underway on this suggestion. The complete report can be found via this link (in Dutch).